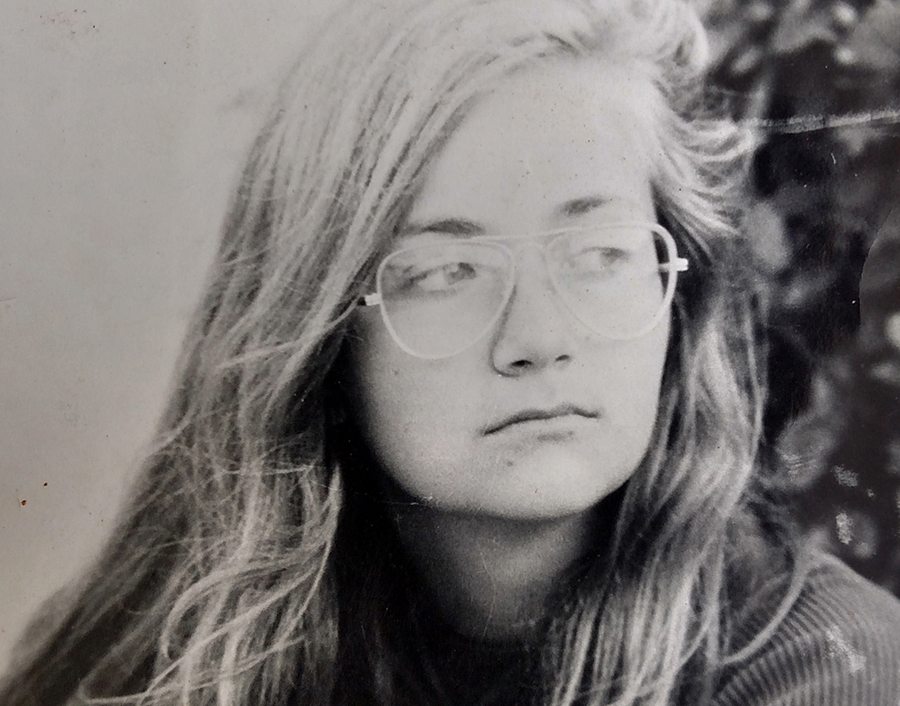

In this photo, I was nineteen. I had been disowned by my father, told I could never return home, wrestling with depression, speaking with sarcasm, and impacted by child abuse. Writing my memoir was a way to help me make sense of ‘her’ life and to help others.

When I realized I was writing a memoir that centered around my relationship with my father, I knew I was both writing about my life as an architect’s daughter and also an abused child. I needed to find my way to write about both of these worlds, and I needed to find a way to understand what had happened.

Fortunately my third grad school mentor, Richard Hoffman, had written his memoir about a sexual predator and his childhood abuse. He was a safe listener as I started writing. The stories poured out, including ones I’d never told anyone. Maybe scarier than writing about the bad things that happened with my father was to write about how I’d loved him. I had adored him more than anyone in my childhood. It was painful to return to the heartbreak of loving and hating him, and the decades of breaking away and reconnecting. I had felt free of him the day he died. I was afraid I might be seduced again by his world of wines, sports cars, art and modern architecture. I was afraid of getting caught in the old pain.

I read Richard’s essay “What’s Love Got to Do With It?” about his abuse experience with a pedosceles (his corrected name for what our culture called pedophiles). My bitter truth was that my abuser was my father. I struggled to love him for forty years. I sank into a painful despairing place. I needed help on how to hold my center while writing this story.

I met with Alexandra Merrill, in her 70’s, a feminist educator who works with women leaders internationally. I had worked with her as a counselor and in woman’s leadership training groups for 20 years. She strengthened my ear for being aware of issues of class, race, gender, illness and healing. I wanted her perspective on how to hold the vast polarities in my experience with my father as I wrote the memoir.

Alexandra supported me in holding the widest view I could of who my father was and how I related to him. My father was bi-polar, a sex addict who harmed several teenagers, and mentally/ emotionally/ and spiritually abusive as a parent. He was also a charismatic brilliant architect, receiving the AIA lifetime achievement award for his impact on modern architecture, creating modern buildings amidst great controversy in the city of Cincinnati. He was my father who loved, abused and trained me through intellectual seduction, grooming my mind like in The Prime of Miss Jean Brody.

Alexandra helped me see that I needed to place his story in the context of German immigrants, children growing up in wartime, the history of women trained as courtesans to intellectually engage with men, Victorians and the Modern era, and when art was God. I was writing about the interweaving of race, class, and culture in Cincinnati and in the village of Glendale where we lived from the 1950’s to the 19 70’s. Underneath the story runs the devastating chronicle of misogyny. Yet, ultimately the purpose of my exploration was for healing. She helped me return to my intent, to create a wide enough view to hold the complexity of my relationship with my father. I wrote as fast as I could to catch her words about my father:

The good whole part of your dad was eclipsed and not treated. He was brilliant and had an ebulliant enthusiasm that attracted people to him. But in the culture of his time, the white man prison couldn’t tolerate the place of his radical artist, and it made him crazy. He was raised during WW I, a product of immigration, his grandparents came here to escape from war in Germany, he was raised in a catastrophic time. At birth his mother went into a darkened room for three years, his grandmother who cared for him died when he was five and he was never held or cared for by a woman again as a child. That is trauma. No wonder he became enamored with skin and touch. A German tyrant father raised him, and he became a tyrant. He was fundamentally a good person, knocked off balance way too early with no one holding him, so he went nuts. The deeper story doesn’t excuse the behavior, but you can have compassionate understanding. You still have your pain and wounding with your own healing to do.

Her voice of understanding helped hold me steady. I returned with a renewed commitment to write all the memories that surfaced.

When I worried whether anyone would want to read another memoir dealing with trauma, William Zinsser’s essay on successful recent memoirs helped me better understand what I was intending to do. As he described what these writers had accomplished, he strengthened my courage to trust what I was doing. He helped me battle my doubts. Why in the world are you doing this? How could you have loved this terrible man, your father? Zinsser countered this voice.

“If these books… represent the new memoir at its best, it’s because they are written with love. They elevate the pain of the past with forgiveness, arriving at a truth about families in various stages of brokenness. There’s no self-pity, no whining, no hunger for revenge; the writers are as honest about their own young selves as they are about the sins of their elders. …They want us to know.. we have endured to tell the story without judgment and to get on with our lives.”

Zinsser’s words were like a balm for me, a blessing. He assured me that it was right to do what I was attempting to do. I was discovering the heart of my memoir was ultimately about love and understanding.

A few years later after grad school, when I had a first draft of the memoir, really an ungainly rough pile of three years of writing memories, chapters, dreams, rough starts and experimentation, I worked with my first editor Nina Ryan, to help me focus the memoir. She pointed out the tension that I was wrestling with throughout the story.

…the primary challenge of a revision is to answer the question: what is this book about? Which story is it—the story of the architect’s daughter, or the story of the abusive tyrant’s daughter, or is it both? Your father was a charismatic, successful, architect, a visionary, romantic and larger-than-life figure. He was also a tyrant, mentally ill, abusive, out of control and out of bounds in his behavior in ways that destroyed his family and his life. You paint him as a tragic figure, and I think he is—the most powerful chapters in the book capture your father’s tragedy, and also your mother’s grit and strength.

What does it mean to be, “my father’s daughter;” to be the hero’s daughter: Odysseus’ daughter; to be the architect’s daughter; to be the tyrant’s daughter; to be the monster’s daughter?

As I began the next complete revision, finding order in the hodge-podge of three hundred pages, I found I could breathe easier. The river of memories had quieted. The memoir was clarifying into a portrait of a girl becoming a woman, caught between adoring and breaking free of her brilliant, destructive architect father. As I clarified and deepened my voice, I continued to heal. And I had so much more work to do, to understand and write the whole story, as best I could.

OMG! Elizabeth! This is so powerful! No wonder I’m scared to read the book! What a journey of discovery and healing! Thank you! I’ll get there yet.