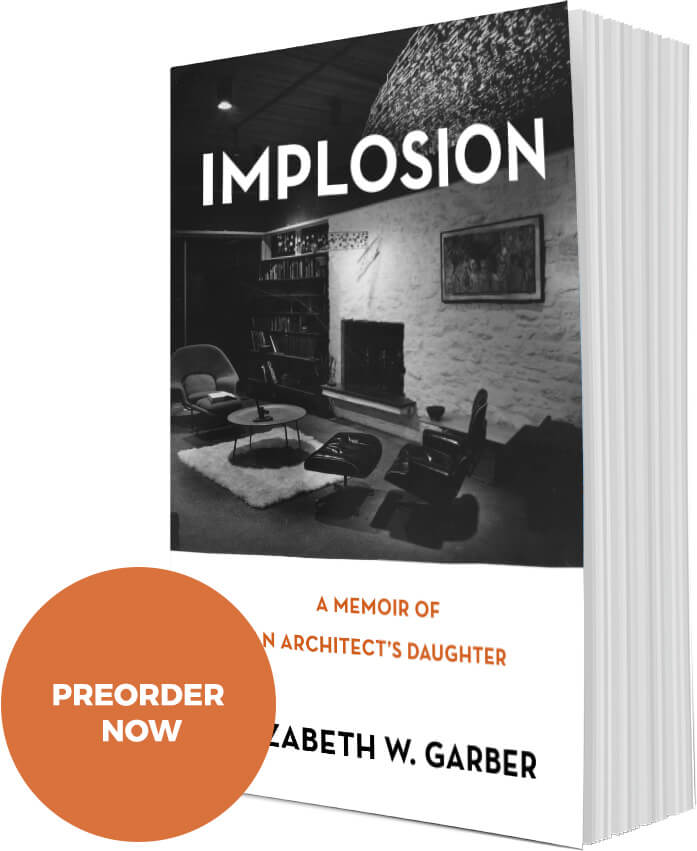

An Excerpt from Implosion: A Memoir of an Architect’s Daughter

One June morning in 1991, three years before my father died, I was working in the garden with my children playing nearby. I had no idea my father was standing on a house boat anchored at a precise location in the earth-brown Ohio River. He mentioned it casually over the phone a week later, as I spooned oatmeal for my one-year-old daughter. He said, “We met early at the dock.” Bob, the mechanical engi- neer for Sander Hall, had helped my father aboard, before motoring downstream until he angled his boat into position, out of the current. Tugs rumbled by, maneuvering barges piled with small mountains of glistening coal.

My father, nearly eighty, his back curved over from os- teoporosis, had brought a bottle of chilled champagne. They trained their binoculars on the top floors of the mirror glass dorm that appeared, like a Japanese kite, flying high above the tree-covered hillside. They checked their watches and looked up every few seconds.

From that distance the tower had appeared as beautiful as my father had envisioned it, silvery rose mirrored walls rising high above the earthly world, where clouds floated over the surface, like the painting I’d seen in his office, a building sur- rounded with grass and trees. But my father’s grand vision had been hijacked by a miasma of circumstances. The tower was inextricably knotted into a collision of 1970s radical social change, wealth and poverty, racial inequality, and battles be- tween administration and students in a roaring fury against the establishment that Sander Hall represented.

After I left home I’d heard occasional reports on Sander Hall. It was known for an epidemic of arson. Smoke rising up stairwells. Smoke seeping into dorm rooms. Eleven years af- ter it was opened, a panicked girl used her desk chair to smash through the mirror glass wall of her sixth floor room to escape the smoke. Firemen on a ladder lifted her down. The University closed the building.

Studies battled over the fire safety of the dorm. Did it meet state code? What could be done to increase the safety of the building? Add an additional stairwell at the end of the building? Newspaper articles debating the issues stacked up on my aging father’s desk. An occasional letter to the editor praised the building and declared it was the students who had been the problem. The university considered changing the tower over to administrative offices. But the price tag for renovation came back nearly the same as for a new building.

The University finally abandoned the building, leaving it to stand empty, a dark derelict tower, a shadow hanging over the University for nine years. Twenty years after the hall opened, in 1991, the President of the University was quoted in The Cincinnati Enquirer: “If I didn’t know better, I’d say the building was haunted.”

Throughout my childhood my father always declared, “I’ll be an architect until the day I die. It’s in my blood.” Yet no one could have guessed in the weeks before the ribbon- cutting ceremony for Sander Hall that the financial recession of the 1970s would halt major construction in the U.S. for years. In 1971, Sander Hall looked like the pinnacle of Woodie’s success, with the promise of more work to come. His career began with a glass tower that was never built and ended with the completion of a glass tower when he was fifty-eight. He held onto his empty office for a few years, finding consulting work, and finally, he taught a few classes to architectural stu- dents at Miami University.

On campus the crowds started gathering hours before. Some had stayed up all night partying and waiting. They pushed up close to the police barricades. Mid-June, Saturday morning, the University of Cincinnati campus should have been sleepy and quiet on summer school schedule. But surround- ing the campus on flat roofs of cheap apartments, students clasped mugs of coffee and munched on bagels. Figures lined the top floors of University buildings. Crowds lined Calhoun in front of bookstores, head shops and the falafel shop where they would put up a framed series of second-by-second pho- tographs of that day. Everyone waited, their eyes tracing the familiar high-rise dorm, Sander Hall, which had stood on the east side of campus since the turbulent early 1970s.

Twenty-seven stories tall, a grid of strong vertical lines with horizontal mirrored panels from an era famed for glass buildings, the dorm reflected two church steeples, pearly clouds, and plumes of airplanes across its glistening surface. On either side of the building, the column of windows was edged with my father’s invention, crushed milk-glass panels, made in Xenia, Ohio, sparkling when the sun cut through Midwestern cloud cover. Two years after the tower was completed, a tornado destroyed the town of Xenia and the plant where the panels were constructed. The panels were never used on any other building besides our home and this dormitory.

The only skyscraper outside of downtown, like an arrow on a compass, the gleaming tower could orient you even from miles away. “Oh, there’s campus,” you would say to yourself. While driving along Columbia Parkway edging the Ohio River, when the steep hills and wooded ravines tucked just right, you could catch a glimpse of the upper half of the tower, just for a moment.

That morning, everybody had their opinions of the building; the same rumors, questions, and curses multiplied like flies, a cacophony of murmurs across every crowded hill- side.

“Man, who the fuck ever wanted to live twenty-seven floors up?”

“There were fires in there. I heard someone died!”

“Some people tried smashing open their windows.”

“Did anyone jump?”

“Whoever would have designed such a thing?”

“A damned eyesore!”

He would later document, in his last Literary Club paper, the first half of his ill-fated journey, trapped aboard a forty- foot yacht under the command of an abusive and inconsistent captain who risked their lives and held their passports so they couldn’t leave. At the same time a common medication, In- derol, prescribed preventatively to keep his heart steady on the journey, was withering him. After six months at sea he returned, a collapsed skeleton of an old man, repeating every sentence three times, apparently terminally ill until he stopped the medication. He sued the doctor and lost. With his complicated cardiac and mental health history, it was im- possible to prove the cause of his collapse.

He would recover slowly, and for a few years began to rebuild a life; learning how to use a computer, he’d stay up till dawn. But years of isolation and depression took their toll, and he began to sink. His teeth were failing, and his den- tist convinced him to pull them all out and have implants screwed into the bone. This would turn into a year of tor- ture, sleepless on pain meds and antibiotics, gums swollen and infected, a liquid diet, health robbed again. He wouldn’t recover this time, despite the wall of perfect teeth imbedded in his withering face. By the end his spine betrayed him, crumbling and caving in before cancer settled into his colon. This was the man who sat in the middle of the Ohio River that June day, looking up at the tower that had consumed all of our lives.

Sander Hall took seven seconds to fall. Young voices cheered what might no longer be cheered, a chilling first practice in watching a modern glass-sheathed building shud- der and wobble like a woman fainting or shot. Still managing to keep her dignity as she stayed upright, she sank to her knees before vanishing in a tsunami of dust that pursued the onlookers. Online, you can play and replay four screens show- ing the single largest implosion in the western hemisphere. Five hundred and twenty pounds of dynamite carefully placed. Six months to plan. Seconds to fall.

On the houseboat, they raised their glasses to toast. White dust puffed gossamer between deep green hills where the tower had held the view for twenty years. My father said over the phone to me a week later, “Good riddance.” His voice still defiant. Interviews in the paper quoted him saying, “I still believe it was a perfect building. Even with all those fires set, a student never died in it.”

Yet I imagined him looking down, tracing his foot along a seam in the deck, muttering quietly, “It’s a terrible thing to outlive your buildings.”