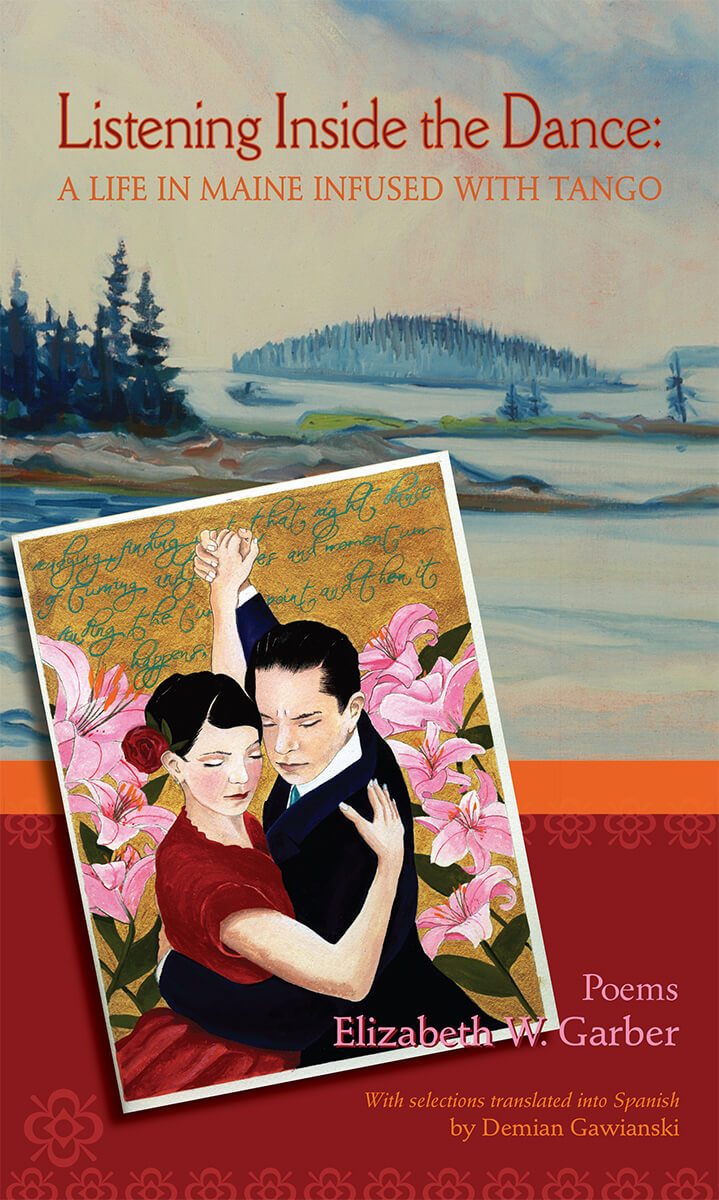

Book Cover painting of Maine shared by Brita Holmquist and for more information about her work go to britaholmquist.com

Painting of Tango Dancers was painted by James Strickland for this book cover. For more information go to jamesstricklandart.com

Listening Inside the Dance

A Life in Maine Infused with Tango

Elizabeth Garber’s second collection of poems takes us into a vivid exploration of another year in Maine and begins with the piercing beauty of the landscape in fall and winter as the backdrop to an exploration of aging. These richly compelling poems explore friendships and family, love and loneliness, and the delight of each moment. At the cusp of spring, she and her fourteen-year-old daughter leave for Buenos Aires and her poems begin to trace with a vibrant poignancy a remarkable mother/daughter journey into Argentine Tango. This section of poems is skillfully translated by Demian Gawainski into the Spanish of Argentina to incorporate the sound and spirit of the city and the people Elizabeth Garber and her daughter meet and study with. The poems then tenderly follow the struggle to return to the isolation of Maine and to integrate what she’s learned into her life at home. The poems end with a magical summer week on an island and take us to a deeper listening into time and life. We emerge from this collection with a better understanding that our lives are a dance that we don’t want to miss.

Praise for Listening Inside the Dance

“It’s a long way from the snows of Maine to the tango and traffic of Buenos Aires but Elizabeth Garber’s poems make the journey seem, at once, plausible and magical. She is a deeply appreciative writer, one who notices with delight and sometimes sadness but who never stops looking and feeling. Her poems throb and glint with the passion of dance and the sweet, sure gravity of meditation.”

—Baron Wormser, Maine’s Poet Laureate

“When I heard about the existence of a woman in New England writing poems in English about Tango and my city, I saw these poems as a brave new genre of this Tango literature becoming universal. But after I started reading the poems and became more immersed in their depth, this intellectualization of a new shape for tango poetry lost its relevance in the pure music of the text. In this stunning portrait of everyday life, this sensitive woman passed through our culture with eyes open enough to see what in other eyes would be a chronic blindness, with a mind capable enough of really learning, with enough gratitude to respond to what she received with such a remarkable creative leap.”

—The translator of these poems, Demian Gawianski

EXCERPT

My Daughter at the Milonga

Six months before, my fourteen-year-old daughter had said,

“I want to learn Argentine Tango more than anything in the world.”

Amazed, I answer, “Really? Well, I think that’s the kind of thing

you do when you are in college.”

But that line of hers stayed with me,

working under the current of my days.

Now I find myself at the crowded edge at El Beso,

in the midnight smoky blue haze of this cozy small dance club.

The dance floor is packed with men, dapper in low double-breasted suits,

and the women sleek, bare backs criss-crossed with thin straps,

flowing legs in silk, feet adorned in jewels of handmade shoes.

My daughter is ready to dance. Stately and graceful beyond her years,

three years of ballroom dance make her facile and quick with new steps.

Relaxing out of the rigid arching back frame of American tango,

she has softened into this very different stance,

stepping cautiously into this first night to dance in close embrace.

We’ve been coached in the dance of eyes that mark an invitation to dance.

She says, “It’s so funny, Mom. In the States, if you like someone you don’t

look at them. Here I just look around and people are looking at me.”

She kept looking back down for awhile, and then with a friend,

they stood up together, eyes softly open, glancing slowly about,

available, ready to dance.

The first man catches her eye, comes up

bowing his head slightly. She glances back a moment at me,

and then they are off to the floor, entering the slow moving circling

of bodies dissolved into an architecture of movement.

I see her for moments through the figures.

Her hair glinting golden, her face uplifted,

her skirt twirling as she turns and follows.

They pause between dances. She chats in Spanish,

saying she’s from a little town of 6,000 in Neuva Inglaterra,

before they dance again, until the series is over,

when she is returned to me.

Each next dancer who invites her to dance is better,

a better leader, and she likes the last best.

She says he reminds her of her dad.

Then it’s time for my big girl and me

to walk home arm in arm to our room.

She leans against me at bedtime,

asks me to brush her long hair.

We lie down in our twin beds to sleep.

“Night, night, mommy. Thank you so much.”

“Good night, sweetheart.”