When Implosion is released in 2018 and I give readings in Ohio, I look forward to seeing the many recent successes in the revitalization of downtown Cincinnati. This is an account of one of my research trips for the Memoir in 2010.

As the plane lowered for a long descent, I felt a flush of excitement as we crossed the familiar blue brown Ohio river and the high hills it has carved for millennia. When we landed in Kentucky, the stewardess welcomed us to the greater Cincinnati area in a curious way, saying “and if you are returning home, I wish you a good homecoming.”

I wasn’t sure I would ever come back after my father died nearly two decades ago, yet I had returned, this time as an architect’s daughter, searching for what remained of my father’s legacy of modern architecture.

I had a few plans for the week but mostly I was making it up, going where I was drawn. From the moment I descended the steep highway through northern Kentucky leading towards the new skyline of my old city, I felt exhilarated.

Cities continually remake themselves. Each new generation of new buildings fling themselves upon the sky line, determined to stand out, to cast a strong impression, to fill their block with impressive design and claim a life and space for the people who will live within their build walls. The city creates a continually changing patchwork quilt of the new jockeying for position around the old pre-existing structures. It is a kind of living sculpture of relationships.

*********

Having lived a quarter century in rural Maine, when arrived in 2010 to explore what remained of my father’s legacy of modern architecture, I was shocked by the magnitude of change since I’d left in the 1970’s. The eternal steady presence of the Ohio River slips through a downtown leaping with post-Modern stone and glass towers, while the waterfront is dominated by pair of stadiums. Leaving the riverbank, I drove through rings of history. The busy downtown is built with the solid foundation of late19th century business and commerce interspersed with conservative 20th century commercial blocks.

Proceeding towards the hills, the prosperity of the city vanished into a wide belted ring of devastation, a wasteland of disintegrating brownstones interspersed with countless blocks of rubble. In the 1970’s, I remember the four story brick row houses that ascended the hills were filled with families, hippies, recent immigrants from Appalachia and the south, integrated neighborhoods with busy corner stores. Now these streets were corridors of abandoned buildings, without a sign of life or business or curtain in a window. I would learn how over a few decades, owners stopped repairs and thousands of buildings drifted into unlivable conditions as their occupants fell casualty to the grind of poverty and unemployment, drugs, crime and police discrimination which led to a new wave of riots.

My initial shock and grief gave way to enchantment as I followed tree lined parkways winding along the river, where yellowing sycamore leaves waved high above their white peeling trunks. Stretching out like fingers winding up and around the hills of Cincinnati, I would explore all week, moved by the variety and beauty of the built and natural environment of the city. I asked myself, what stands the test of time? Under oaks and maples substantial houses of 1890’s through the 1920’s, solidly built brick homes with distinctive variations, substantial porches, bay windows, rounded side towers rising up to a decorative slate roof. They were carefully built with yellow glazed brick, high fired deep red brick, and stone. The buildings of my grandfather’s firm, Garber & Woodward, the solid enduring Beaux Arts towers and schools will soon pass their first century with flying colors. My search was for the fate of my father’s legacy of modern innovation.

I discovered the tireless work of the city’s preservationists and social activists devoted to responding to the mass disintegration of areas of the city’s architectural heritage. When I arrived at my cousin’s home, she gave me a newsletter from Cincinnati Preservation Association where the title article compared the similarities between Cincinnati and New Orleans, linked by historic travel upriver and distinctive architectural styles. Both cities share vast swaths of abandoned houses created by storms of a different kind, both from decades of neglectful policy. Now the preservationists from New Orleans were offering Cincinnati hope and examples of the power of preservation to transform neighborhoods.

In the middle of the packed issue devoted to saving treasures of the nineteenth century was an article on an attempt to save the children’s chapel my father, Woodie Garber, had designed in the mid 1960’s. Written by the architectural historian Professor Patrick Snadon from the University of Cincinnati, he is documenting how mid-century modern buildings have entered the endangered species list. Historians are now trying to educate and create an appreciation for modernism in a new generation. The precarious balance of architecture and my journey had come together.

My week would reveal how the work of my father, Woodie Garber, the most innovative modernist in Cincinnati, was disappearing at an astonishing rate due to the same forces of conservatism that he battled with from the 1950s to 1970s to make sure his buildings were built. My compassion for my father grows with an increased understanding of the fight he lived through his whole career. Some of his buildings are being left like patients in the back hallways of an emergency room while decisions are being made to ignore them until they decline past any help. Others are being dismantled or changed beyond recognition. Few will survive for long in the 21st century.

I met Patrick Snadon, who is documenting my father’s work before it disappears, at Christ Church Glendale where my family had gone to church for three generations. In the 1960s my father designed a modern complex of offices, school rooms and a children’s chapel, tying together the Gothic Church and Parish House. From Patrick’s professional perspective, the modern complex “forms one of the finest Modernist ecclesiastical commissions in the region and in probably the State of Ohio. They are also of national significance. Not only are they splendidly designed and surpassingly beautiful, but the materials and workmanship are superb. Also, they form both a brilliant contrast and a sensitive contextual relationship with the older, Victorian Gothic church to which they were added. This type of contextual response to an existing, older building is unusual for Modernism, which raises the importance of the complex even more.”

As we walked throughout the modern addition, I noticed what I wouldn’t have seen as a child or at twelve when I was preparing for communion. Transparent walls emphasize the garden space where a slender gingko tree fans yellow leaves beside the original 1860’s stone church. The Sunday school classrooms face the garden filled with light even on a rainy day. When I put my hand on the burnished steel railing that follows the steps up three levels, I remembered my little hand in smudged white gloves.

The children’s chapel roof lifts off as lightly as I remembered. The hand blown glass sends bright streams of light that now remind me of the swaths of light in Le Corbusier’s cathedral at Ronchamps. Patrick pointed out the fine masonry in the stone walls and wondered if there are masons who can still do this quality of work. The altar, once solid block of white marble had been replaced by a dark carved wooden table, the simple children’s benches were replaced with a mismatched collection of chairs for adults. I found one remaining children’s bench my father designed and I sat on the smooth curve and found comfort gazing around the chapel as I had as a child.

Yet the church voted to tear it all down because of maintenance issues and heating costs, and because of a lasting vehemence against early modernism. Their initial proposed replacement design presented for the approval at the Glendale Historic Preservation board looked like a brick McMansion. I heard the board turned it down instantly, calling it an appalling design with no sensitivity to the Gothic stone buildings on either side. The economic crash of 2008 slowed down their plans for demolition. Before we left, Patrick wandered off to take more photographs in case the building’s fate would be cast before he can return. I returned back to the chapel to sit on the remaining children’s bench to say goodbye.

(Note: In 2014, the 1960s modern complex was demolished and replaced with a handsome new addition. When I study the photographs I see many echoes of the earlier modern design.)

I remembered driving with my father up a certain tree lined street in Glendale when he parked on the side of the road and pointed at a petite flat-roofed wood and glass paneled house surrounded by trees. “That’s one of the earliest houses I designed before you were born, for a wonderful young couple. We built it on a very modest budget.” Fifty years later, I pull into the drive and walk to the door. The redwood wall panels and clearstory windows seem in fine shape. A weary-looking man opens the door a crack, behind him a slice of wooden cabinets and a haze of cigarette smoke. He looked at me suspiciously. “Yeah,” he snarled, “Woodie Garber designed this. It’s terrible for this climate. They say he was a California Modernist. Well, he should of just gone back there and stayed.”

This is a theme I will encounter again, an open hostility against modern design, yet part of the legacy of modernism back to Le Corbusier, is that sometimes their visionary designs aren’t easy to live in.

As I drive out of the city, the highway slices through a tidal wave of suburban sprawl it helped extend. Perhaps a tragedy of the last half century is this proliferation of un-designed pseudo architecture: fake colonial, fake half-timber, fake plantation pillars and the repetitious blur of malls; an era of buildings never to be walked by, only driven by on the way to the interstate. In these outer rings of highway, you could grow up and never see any true architecture or a true forest or garden, even though they are named by recombining of the same idyllic words, Forest, Garden, Grove, Dale, Lawn, Wood.

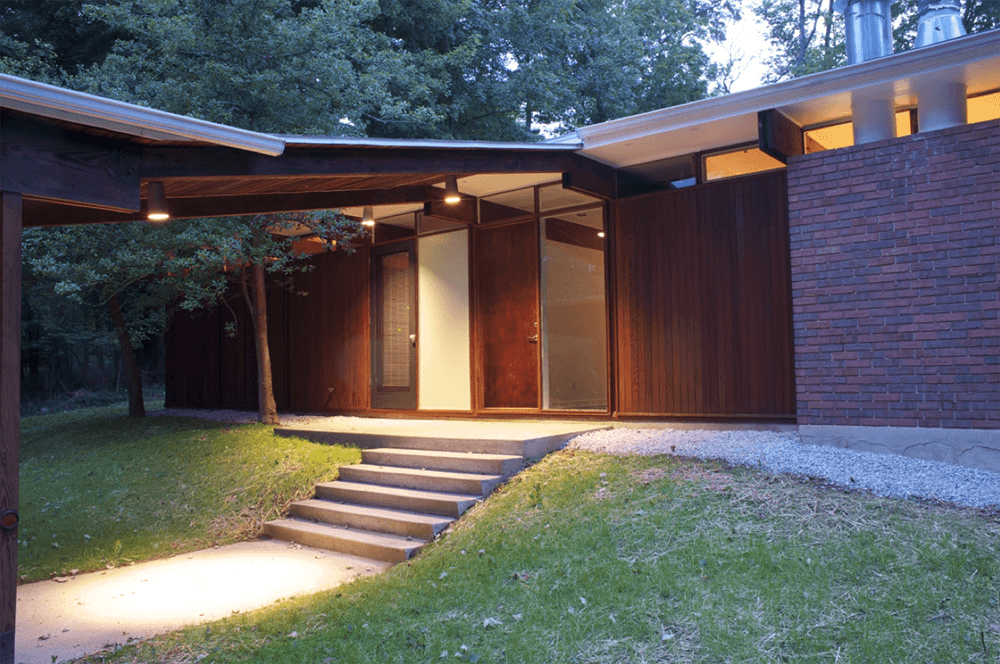

I drive hours north to discover the fate of my father’s design for an affordable professor’s home I last visited in the early 1970’s. A simple flat roofed layout, with redwood panels and glass walls, I remembered how it looked out over a gracious curving lawn, edged with a stone wall and well stacked wood piles to supply the fireplace. On arriving thirty years later, I discover a huge tree collapsed across the front lawn, the drive overgrown and the house abandoned for years after the deaths of the original owners.

Yet in the years after my visit, I hear it has been purchased by a neighbor and I receive photos of a thorough renovation that leaves it a glowing and updated showcase of midcentury modern.

Photo by Gregory Spaid

Photo by Gregory Spaid

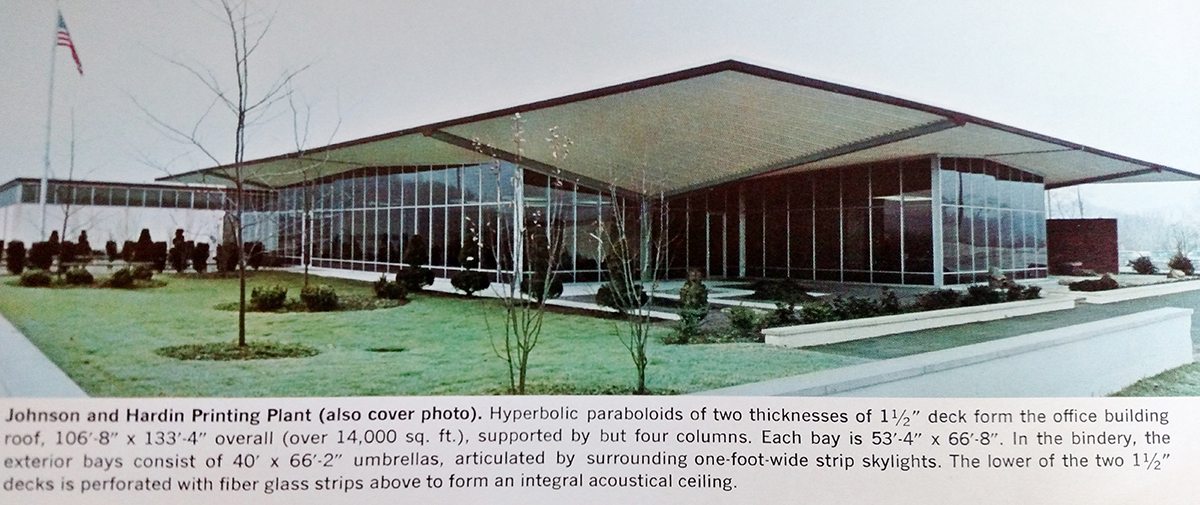

Each day becomes a scavenger hunt as I search my memory and articles for other buildings I visited as a child. I have black and white photographs of corrugated steel roof panels being installed, documenting the excitement in the sixties of the promise of new industry on freshly bulldozed fields alongside new highways. This was a printing plant with a complex roof system based on the designs of the Mexican architect Felix Candella my father had visited in the 1950’s. The building was placed on a bluff over the highway, the graceful corporate offices, complete with a garden terrace, were connected to the plant by a walkway.

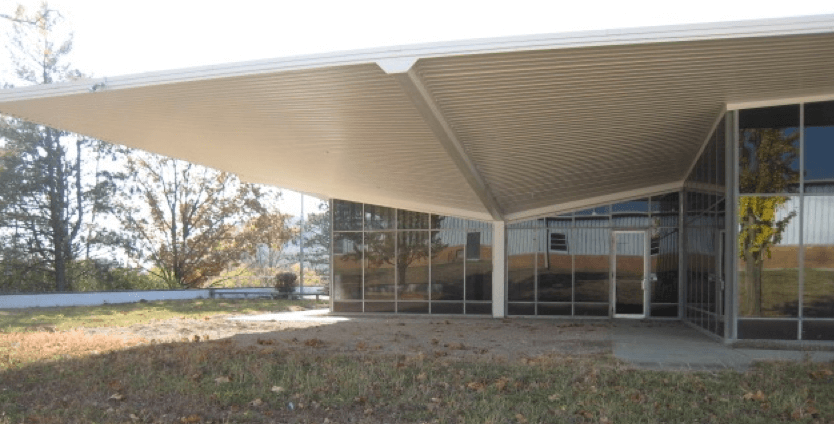

Although the company no longer exists, I locate the address of the former Johnson Harding printing plant off Red Bank Road. When I drive up to the offices and peer in the door I discover the interiors are stripped and pilled high with stored crates. The plant is a now a discount warehouse filled with used office equipment, wheel chairs and discarded computers. Despite the change in function, the design of the building impressive and worthy of study. My architectural companions, Patrick and Udo Greinacher, another architectural professor, are astounded by my father’s design for hyperbolic parabaloid roofs manufactured by Armco Steel. They pace out the distance with their feet, unable to believe these lightweight roof sections, supported by one center post span sixty feet. The curtain walls are a line of well proportioned glass panels alternating with finely mortared brick, even though the mirror glass now reflects a line of derelict warehouses next door. We study the engineering of the roof, trying to decipher of the mind of the architect and structural engineer, as if tracking their minds at work. It was the only factory my father would design, a challenge he leapt to solve where the function so clearly defined the form.

I was excited to show Patrick and Udo what I think is my father’s most spectacular house designs, the third and maybe the last remaining house he designed in Indian Hill. The Klausmeyer family loved their “upside down” summer house on Nantucket that my family visited when I was a girl, and they asked Woodie to create a glass house for them on a wooded hillside. I remembered a long curving drive between tall trees, reaching a carport, and then a series of covered stairs to a two story transparent glass box supported by a narrow white grid framing doors and windows. Covered by a flat roof, the interior space floated different levels for living, cooking and sleeping.

Photo by George Stille

When we visited when I was a child and teen, Ruth welcomed us in, light filtered through the forest canopy and the parquet floor set off her brilliantly colored rya rugs. I thought her sons were exotic teenagers who descended to their downstairs bedrooms to play classical guitar or build sculpture until dinner. I walked around the glass room, climbing stairs to the different levels, to look at their abstract paintings and sculpture. As we drove away after a lively dinner, my father to pull over on the road below so we could look up to see the house lit up like a lantern in the forest. Simply spectacular.

I had made several calls to the new owners with no response, so we were going unannounced to see the house. Patrick turned down the narrow wooded drive and when the car port and house came into view, my heart sank. A metal fence skirts the exterior of the house, a padlocked gate at the top of the stairs, the flat roof is growing moss and grass, the deck is a jumble of furniture, the house jammed with stuff. Was this another derelict house? No, a man with a dog was ascending the stairs. I introduced myself and my companions. He explained he is a renter, and also works for the university, friend of the owner, and who after examining Patrick and Udo’s university IDs invited us to walk around the exterior. Despite green mold staining the white framework of the stairway and the transparent panel overhead, despite the obvious need of attention to the exterior panels, the house is still spectacular.

He explained, as if asking for our sympathetic understanding, “It was really hard to move in here. It’s so small and we came from a big house. We had to squeeze all our things in.” The narrow windows behind the kitchen were lined with a collection of china teapots. As we circled the house every window ledge was lined with objects, a line of beer steins with faces, vases, framed photos. The man told us he had no intention of fixing anything, nor did the owner. He’d rent here a couple more years and then he imagined the owner would demolish the building.

Patrick, Udo, and I were sobered by this news as we drove back to the city. Facing the carelessness attitude of Americans, the thoughtless wastefulness of a throwaway culture, the mentality of why fix it, just tear it down in the context of a museum quality building was excruciating. Patrick sighed, “Sometimes I just feel worn out by it all.” But soon they were strategizing about what preservationist organization or grants could be written to purchase and save this glass cube. How much time left do they have? Udo sighed, “I could really see myself living here.” Patrick had fallen in love with the Moore house when they were documenting it before it was demolished a few years ago. Two long glass rectangular spaces with a glass bridge connecting them, white stone walls, and a 100 foot precipice to a creek below. After the house was torn down, five McMansions were built on the site. Patrick mused, “There are few happy endings in historical preservation.”

Later as I drove through Eden park, I came upon a photographer and ballet students on a photo shoot on a ruin of an old bridge. Their delight and laughter, the magic of being present for such a moment in time with the lovely old buildings of Mt. Adams in the distance, reminded me of the constancy of change, and of each new generation making their own discoveries and bringing their visions into play.

Elizabeth,

Coming across this week’s article about your upcoming talk in Belfast, I decided to google your dad…and for the last hour have just been mesmerized by his/your story. Especially this one as your documentation of the destruction of his work reminded me of my long time held young girl dream of building a glass house. It would have looked much as your dads did.

And, I sill want to build my house…

Thanks

Cecile

Thanks for writing Cecile. So glad you found these stories so compelling, and so glad you remembered your childhood dream! Who knows, you might still build your glass house! Elizabeth

Elizabeth,

As a native Cincinnatian now living in Maine for nearly 20 years, your article resonates deeply with me. I get “home” twice a year and find myself exhilarated by all the positive changes, and sometimes equally disheartened by things that are no longer there. I do find though, that a younger generation is finding an appreciation for mid century architecture. I wish I would have known more of your fathers work while I lived there. That said, I spent many hours in some nook of the main library on many occasions. I look forward to reading your book, and hoping catch a speaking engagement in the future.

Alexander Fee

Hello Alexander, yes, it is so heartening to see the positive changes in Cincinnati and the strong interest in midcentury modernism. Thanks so much for responding. It’s amazing how much a city can change in a decade let alone the changes over several decades. ELizabeth