“One of the strange things about teaching is that you can never know what your effect will be on others; [you] can never know…who your real students will be, the ones who will take what you have to give and make it their own…..[The teacher]can never really know which of the young people clustered around the seminar table is someone whom the teacher or the text has touched so deeply.” Pg 241, An Odyssey: A Father, a Son, and an Epic, Daniel Menhelsohn, 2017.

Excerpt from an earlier version of Implosion, Chapter: Odysseus’s Daughter

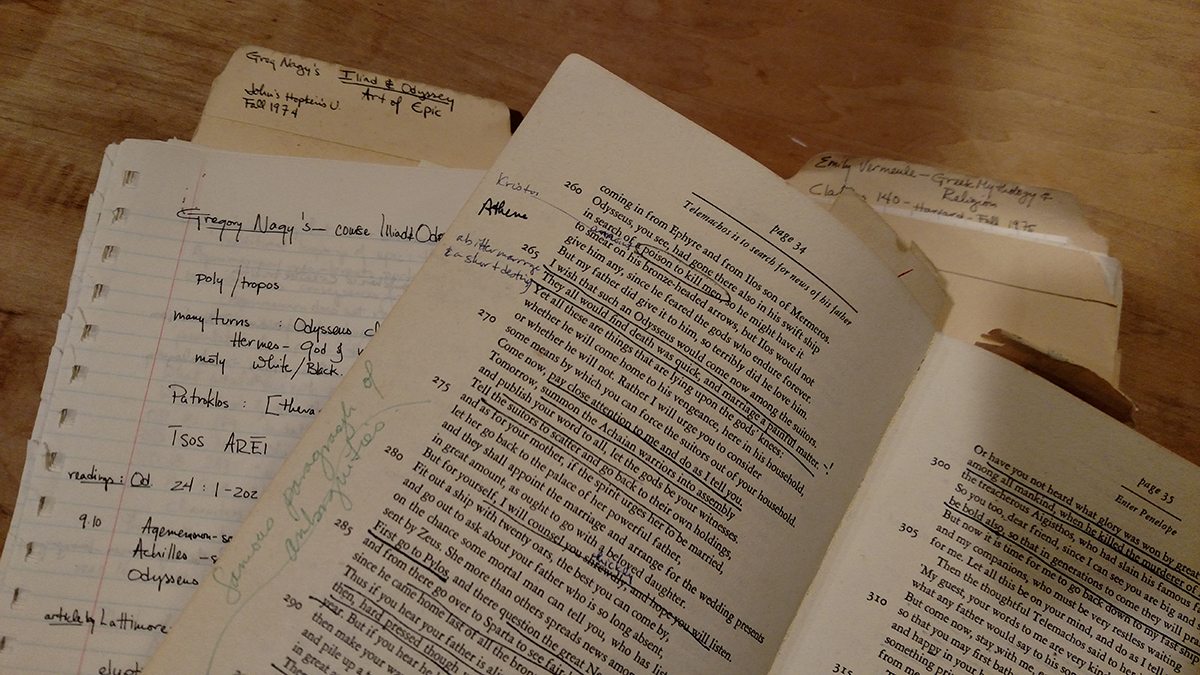

My first semester at Johns Hopkins in 1973, my roommate Jane said I had to join the coolest seminar on The Iliad and the Odyssey. I had missed the first four classes but she gave me her notes and was emphatic, I had to come. I felt awkward as I join the handful of students around a table while the young professor with curling hair and a profile like a Greek hero wrote a word on the board, first in Greek characters and then English. Menos. I was worried.

He explained, “Menos is usually translated as confidence or strength, particularly strength that is breathed in. Athena could breathe menos into a hero. In the beginning of The Odyssey, when she disguised herself to help Telemachos discover the fate of his father, she called herself Mentes. She is encouraging him to become the man he is meant to be.” Professor Nagy (pronounced nadj) continued scrawling words across the board, as he switched effortlessly from English to Greek, Hittite to Indic. His enthusiasm warmed us as we followed his leaps of connection effortlessly.

He continued, “But menos isn’t for heroes only. This breathing strength of mind flows in the sun, in fire, moist winds and rivers.” Dr. Nagy kept going back in time, tracing menos to manas from Indic poetry where it meant not only the strength that made the sun rise and the wind to come but was also the power of the poet, the strength that was breathed in from the cosmos. Professor Nagy paused, the delight in his eyes made them more penetrating. “What is the strength that is latent in you that has to be breathed in by the gods?”

I left the class trembling, as if I’d been a torch soaked in oil and the lecture was the match. All I wanted to do was study The Odyssey and find the underpinnings of earlier mythic stories. With boundless enthusiasm, Dr. Nagy encouraged me. “You’ve got to learn Homeric Greek. I’ll tutor you. Keep at it all summer and you’ll be up to speed by fall so we can continue working together.”

(A year later, Dr. Nagy, given a full professorship, taught at Harvard, and I transferred to continue studying with him.)

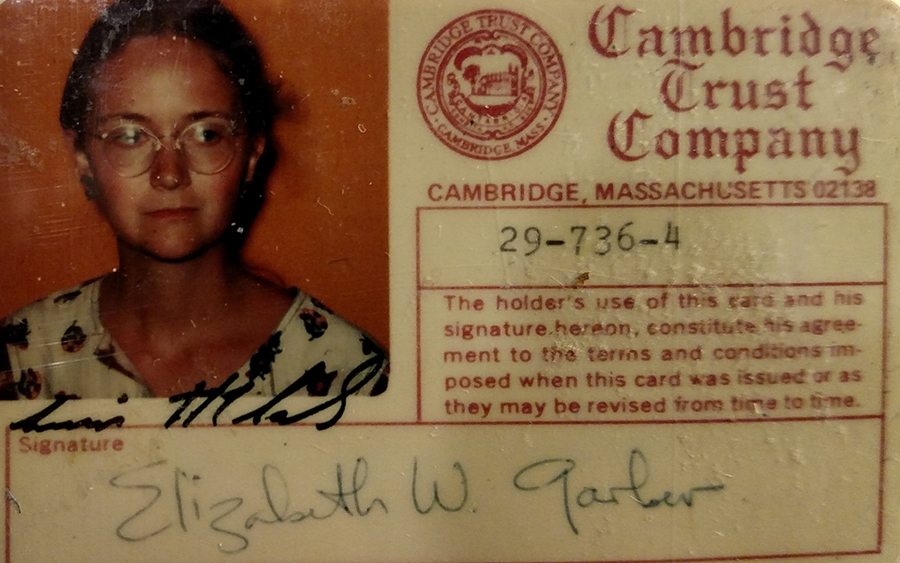

At Harvard’s welcoming reception for transfer students, we were assured we were the cream, beating higher odds than freshmen to be accepted. They expected great things from us. A white-coated waiter carved a massive half side of roasted beef. As he piled slabs of bloody meat on my plate, I thought of Odysseus feasting after offerings had been made to the gods. I wandered back through the labyrinth of Cambridge streets that night, warmed and hopeful.

In a darkened lecture hall looking at slides of Greek vases, late September 1975, I took careful notes as Dr. Emily Vermeule’s commanding voice led us behind the scenes to understand the myths. A mythic figure herself, as a young woman she had discovered a Mycenaean city. “Odysseus is the least heroic of the Greek heroes. He is always the deceitful, malicious liar but also the most mature and eloquent of speakers.” She showed an image of the large-chested hero. “He was a series of contrasts. He arranged that the Trojan War should be fought but then he tried to get out of it by feigning madness.” I imagined him, the young father who tried to escape his destiny. If he left for war, it was foretold he wouldn’t return for twenty years and then as a beggar. “He stole statues from temples, tricked heroes, but he made the Trojan Horse, and so his wit finally won the battle of Troy.”

I was captivated by Odysseus, from the first time I had read him my freshman year. Forty years later I see him as a trickster whose wooden horse brought down the fine and noble city of Troy. But at twenty-two I was captivated by this larger-than-life hero, humbled as he barely survived his journey home. I wasn’t attracted to him like the naïve Princess Nausicaa on the beach waiting for a fine husband, no, he was an older man, old enough to be my father. I didn’t identify with the enduring Penelope holding off the suitors with her grief and wit as best she could. I wasn’t the young Telemachus who sailed off to other island kingdoms to listen for word of his father. I wasn’t Athena watching out for him, steering him as best she could through the Gordian knot of fate so he could be released from the curses of Poseidon for having blinded his son, the Cyclops. No, I loved him like a proud warrior daughter, who would have stood waiting for his return without a doubt, ready to take the spear to vanquish his enemies.

I knew him because I read him, over and over, in English and slowly in Greek. I had no idea then that I had found in Odysseus a man of my father’s stature and moral complexity, but in a story with a happy ending. He succeeded in returning to his loving Penelope. Ever since I’d been a girl, I’d merged with characters in books. In high school I became Cassandra in I Capture the Castle. As I read the Odyssey, I loved him like a daughter, not realizing he was the father I yearned for. In reading, I could see his rage and despair, and they didn’t hurt me. He would triumph in the end, he would conquer death, find his way home, destroy the suitors, return to his wife’s loving arms.

As a child, I had been my father’s companion, accompanying him on his jobs, seeing houses, colleges, and towers emerge from his drawings. Reading the Iliad, I was impressed yet wary of Odysseus making his brilliant strategies in war. I preferred his personal journey in the Odyssey, where I was a quiet companion, privy to his grieving on the beach, his longing to return home. I sat up late, a reading light shining over the page, and wept when the old nurse found the scar on his leg and recognized him. In disguise, when Odysseus saw his adult son for the first time, he was overcome with love and pride. That was the father I still hoped for, who would adore his sons, who would weep with love for them, and with grief for having missed their childhoods.

Reading Homer, I returned to Ithaca before him, knew the goatherd who was still loyal to his beloved master. I knew who was the most despicable of the suitors and waited excitedly for Odysseus’s revenge. After the palace had been cleansed and Penelope had tested him for the last time, after they retired to their bed and the gods held back the night long enough so he could tell her his entire journey home, I wasn’t jealous. I loved him like a loyal daughter who stood sentry over the palace in Ithaca all night. Who else knew him, loved him better than I? I was the daughter who still loved her broken father after no one else remained.

Postscript: Forty-five years later, after I’d written my memoir, I wrote to Dr. Nagy, thanking him for his stimulating classes years before and I included the chapter Odysseus’s Daughter. I told him I was teaching a senior college class on The Odyssey. I’d spent over 100 hours preparing a PowerPoint packed with details for exploring the story, key Greek concepts, as well as art work and maps, to teach five two-hour classes. I used my notes from the 1970’s, studied Dr. Nagy’s book on The Greek Hero, and compared several translations. I was more captivated by the Odyssey than ever, and in my 60’s, I poured my enthusiasm and excitement into teaching The Odyssey, catching up with my old dream to be a classics professor.

Studying Odysseus still helps me understand my father. As I read Dr. Nagy’s translation of the first lines of the Odyssey, I still find my father in this ethically complex, difficult and fascinating hero. But I’m not a young woman yearning for her father and still hoping for his happiness. I’m an older woman, who has seen the span of her father’s life and death, seen his hubris, daring, deceit and harm; a broken yet proud man to the end.

“That man, tell me O Muse the song of that man, who could change in many different ways who he was, that man who in very many ways/veered from his path and wandered off far and wide, after he had destroyed the sacred city of Troy./Many different cities of many different people did he see, getting to know different ways of thinking [noos]. Many were the pains [algea] he suffered in his heart [thumos] while crossing the sea/stuggling to merit the saving of his own life [psukhe] and his own homecoming [nostos]” Nagy, Gregory, The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours, Harvard University Press, pg 296 Ody. I:1-6

Leave A Comment